The Wethersfield Conference and Aftermath [Editorial Note]

Editorial Note

Soon after Lieutenant General Rochambeau arrived in the United States as commander of the French expeditionary army, he met GW at Hartford to plan how to take New York City from the British. An attack desired for the fall failed to materialize for lack of naval and troop reinforcements. Taking New York City remained a goal as the two men continued communications on strategy.1

Early in 1781, GW and Rochambeau corresponded about plans to dispatch a French fleet to the Chesapeake Bay, where it would cooperate with Major General Lafayette’s corps against British forces under Brig. Gen. Benedict Arnold. GW and Rochambeau discussed these naval operations at Newport in March.2 Their designs failed when a British fleet under Vice Adm. Marriot Arbuthnot overtook the French fleet at Cape Henry, Va., and denied the French access to the bay.3

Hopes for successful combined operations against British forces were revived when Rear Admiral Barras, appointed to command the French squadron, arrived in Boston on 6 May.4 Barras carried private dispatches addressed to Rochambeau from French officials with instructions on the upcoming campaign. The dispatches included King Louis XVI’s decision to grant the United States a significant monetary gift. The instructions also prohibited Rochambeau from marching his army from Rhode Island without securing Barras’s squadron at Newport or Boston. Significantly, the dispatches announced the departure from France of a fleet commanded by Lieutenant General de Grasse, bound for the West Indies, but then to operate with Rochambeau and Barras off the American coast in July or August. Rochambeau was instructed to hold this latter piece of information in the utmost secrecy.5 Breaching the injunction, Major General Chastellux imparted this intelligence to GW.6 The instructions prompted Rochambeau to meet GW to begin planning operations.7

On 13 May, after hearing from Rochambeau, GW selected Wethersfield—a small town south of Hartford and about halfway between his headquarters at New Windsor and the French headquarters at Newport—as the meeting place. A quiet town, Wethersfield was more suitable than Hartford, where the state legislature was in session. Once GW had determined on 21 May as the meeting date, Rochambeau began drafting proposals that reflected his discussions with Barras regarding naval operations.8

GW directed Ralph Pomeroy, deputy quartermaster general for Connecticut, to prepare accommodations in Wethersfield for the two parties.9 Accompanied by brigadier generals Henry Knox and Duportail, GW left New Windsor on 18 May,10 traveled through the Connecticut towns of Kent, New Milford, Washington, and Litchfield, dined in Farmington, and reached Wethersfield on 19 May.11

Newspapers announced GW’s arrival. One report described how the travelers were “escorted into town by a number of Gentlemen from Hartford and Wethersfield. As [GW] dismounted at his Quarters he was saluted by the discharge of thirteen Cannon.”12 From the time of his arrival until his departure on 24 May, GW lodged at the home of Joseph Webb, the owner of a tannery and shoe manufactory. Webb’s home, built in 1752, was located in the center of town. It was likely in one of the front parlors that GW and Rochambeau devised their campaign plans.13

Prior to Rochambeau’s arrival on 21 May, GW met privately with Connecticut governor Jonathan Trumbull, Sr., and Jeremiah Wadsworth, purchaser for the French expeditionary force. Trumbull and Wadsworth expressed confidence that the Americans could secure the men and provisions required for an “important offensive operation.”14 Trumbull recorded in his diary for Sunday, 20 May, that he “attended divine service with General Washington” at the Congregational church in Wethersfield, where the minister preached from Matthew 5:3: “blessed are the poor of spirit, for their’s is the Kingdom of Heaven.”15

Rochambeau and Chastellux left Newport for Wethersfield on 19 May.16 The generals “and their Suites, arrived at Wethersfield” on 21 May. “They were met at Hartford by his Excellency General Washington, the Officers of the Army, and a number of Gentlemen who accompanied them to Wethersfield, where they were saluted with the Discharge of Cannon. Every Mark of Attention and Politeness were shewn their Excellencies and the other Gentlemen of the allied Armies, whilst attending the Convention.”17 During their stay, the French officers lodged at Stillman’s tavern. Besides talks with GW, Rochambeau socialized with high-ranking officials, including the governor, who dined with the two generals on 22 and 23 May. GW and Rochambeau attended a choir concert in their honor on 21 May.18

The French contingent arrived without Barras, who stayed at Newport after British warships had been sighted off Rhode Island loaded with troops bound for the Chesapeake Bay. Barras also wanted to meet a convoy arriving from France with de Grasse’s squadron.19 The admiral’s absence did not hinder the conference because Rochambeau had discussed strategy and goals with Barras and represented his thoughts at Wethersfield.20

Lengthy discussions between GW and Rochambeau took place on 22 May. The primary question addressed was whether the allied armies should march overland and attack the British around the Chesapeake Bay or conduct offensive operations against the British garrison in New York City. As early as March, GW had held the view that without naval superiority or more French troops, the best prospects for success would come from an attack upon the enemy in New York, which he believed would divert British troops away from the southern theater.21 Aware that Barras was not prepared to transport French troops and military material to Virginia, and believing that the British garrison in New York City already had been weakened from the recent detachments,22 GW argued that Rochambeau’s corps should march to the Hudson River “& there, in conjunction with the American, to commence an operation against New York.” GW left open the option of an operation in Virginia if a superior French naval force were to arrive in American waters. Concerns over transportation expenses and potential troop losses during “long marches,” two risks associated with a southern offensive, were among the determining factors behind GW’s preference for operations against nearby New York.23

While at the conference, GW compiled an estimate of the force that would be available for operations against New York: 8,250 if the northern army’s regiments reached full strength. With New York as the objective, GW believed that he could raise an additional 2,000 men and that “there would be no want of Militia.” He approximated enemy strength at New York City at 7,500 regulars, Loyalists, and militia.24

Without a promise of troop reinforcements, Rochambeau was in no position to contest GW’s proposals. His principal objection was the impact that British subversion of the southern states might have on the rest of the country. He also believed that naval reinforcements would be necessary for a successful operation against either New York or Virginia, and he worried that large French ships might not be able to pass Sandy Hook bar. After the conference, Rochambeau revealed to French officials his preference for an offensive in Virginia. Rochambeau subsequently explained that he viewed such an expedition to be “more practicable, and less expected by the enemy.”25

With the conference between the two generals ended, Rochambeau left Wethersfield on 23 May. GW departed the following day for New Windsor, where he arrived “about Sunset” on 25 May. His itinerary included a meal at Farmington, an overnight stay in a tavern at Litchfield, and breakfast in another tavern at Washington.26

GW immediately began campaign preparations. He composed a circular letter that called on the executives of the New England states to raise their required troop quotas and to ready militia.27 Supply officers received requests to make arrangements, and GW consulted a board of general officers. Bateaux construction was begun.28 In addition, GW divulged the campaign strategy to some individuals—a decision that proved fateful when a number of those letters were intercepted by the enemy, revealing allied strategy to the British.29

Convinced that New York City was threatened, British general Henry Clinton wrote Lt. Gen. Charles Cornwallis, commander of the British army in the south, from New York on 19 June: “The intercepted letters which I had the honor to transmit to your Lordship with my dispatch of the 8th instant will have informed you that the French Admiral meant to escape with his fleet to Boston from Rhode Island … and that it was proposed the French army should afterwards join such troops as Mr Washington could assemble for the purpose of making an attempt on this post.

“I have often given it as my opinion to your Lordship that for such an object as this they certainly could raise numbers, but I very much doubt their being able to feed them. I am, however, persuaded they will attempt the investiture of the place. I therefore heartily wish I was more in force that I might be able to take advantage of any false movement they may make in forming it.” Clinton asked Cornwallis to send him reinforcements, if possible, and noted the strong probability that de Grasse would “visit this coast in the hurricane season and bring with him troops as well as ships.”30

In a letter dated 9–12 June, Clinton had written Lord George Germain from New York City that he hoped Cornwallis would attempt a campaign in Pennsylvania, “which I shall recommend immediately. But should his lordship have reasons for declining it and have no other to propose, I shall probably direct him to take such posts in the Chesapeak as he shall judge proper, keep troops sufficient for desultory water expeditions during the summer (when according to one of Mr Washington’s intercepted letters all land operation in the Chesapeak should stop), and draw what troops can be spared from thence to this post, with which I shall act offensively or defensively as circumstances may make necessary.”31 British major Frederick Mackenzie, stationed at New York City, wrote in his diary for 18 June that the Americans planned “to invest New York.” He added: “Every argument is using by Washington to induce the States Northward of the Delaware to contribute their quotas of Men, Money, Stores, provisions, Carriages, horses, &c, &c, to enable him, with the Assistance of the French, to carry this enterprize into immediate execution; but their resourses are so much exhausted, and there is so little unanimity among the people, that he is in great doubt of their complying with his demands.”32

Rochambeau commenced “arrangements for a movement of the troops” upon his return to Newport on 26 or 27 May.33 Like GW, he corresponded with officials about the conference. In a letter to French minister La Luzerne dated 27 May, Rochambeau transmitted in code the proceedings and decisions, and he advised La Luzerne that he had withheld the specific intelligence about de Grasse’s prospects of arriving on the American coast. He had briefly mentioned it only as a possibility. Rochambeau also noted that his troops would march to the Hudson River upon GW’s orders. The British intercepted this letter, which led Rochambeau to enclose a coded duplicate with a letter to LaLuzerne dated 9 June. In that missive, Rochambeau assured the French minister that the intercepted conference proceedings dated 27 May would be unintelligible to the enemy, having also been written in cipher.34 This hopeful conjecture was confirmed in a letter that Clinton wrote Germain regarding “a cipher one from Monsieur Rochambeau to the Chevalier la Luzerne which appears to be very material, but we have hitherto been foiled in our endeavours to discover a key to it.”35

Rochambeau wrote de Grasse on 28 May. According to the French general, GW estimated 8,500 British regulars and 3,000 enemy militia stationed in New York City. Rochambeau reported Barras’s inability to transport troops to the Chesapeake Bay, as well as plans for the allied troops to launch an attack on the British garrison at New York. The French general expressed concerns that both GW’s army and his own corps would prove weak before that British stronghold.36

In a letter dated 29 May, Rochambeau informed French war minister Ségur about a significant alteration to the decision made at the Wethersfield conference to send Barras’s squadron to Boston upon the march of the French army from Newport. At the end of May, a council of war resolved to keep Barras’s squadron at Newport and secure it with more militia. The decision was prompted by a fear that Americans might view the squadron’s anchorage at Boston as a retreat. Additionally, the council argued that at Newport the squadron would be closer to offensive operations.37 Rochambeau again wrote Ségur on 1 June to complain about troop shortages and warned that he would have fewer than 3,000 armed men to join GW’s army. Rochambeau believed that the arrival of the French troops in New York would increase American morale.38

The strategy determined at the Wethersfield conference was never fully implemented. Rochambeau’s army did march to Westchester County, N.Y., in June and formed a junction with GW’s army in early July. The allied troops operated around New York City and unsuccessfully attacked British posts on northern Manhattan Island.39 Lacking naval superiority, the allied armies could not put the British garrison under siege. When de Grasse sailed his fleet to the Chesapeake Bay rather than New York City in late summer, Rochambeau’s preference for an operation in the southern theater, and GW’s willingness to pursue offensive operations there with sufficient naval strength, led to what would become the successful Yorktown campaign.40

2. For GW in Newport, see GW to Alexander Hamilton, 7 March 1781, source note. For the sailing of the French fleet, see Destouches to GW, and Rochambeau to GW, both 25 Feb.; see also GW to Destouches and to Rochambeau, both 2 March.

3. See Destouches to GW, 19 March, source note.

4. See Barras to GW, 11 May.

5. For these dispatches, see Rochambeau to GW, 11 May, and n.2 to that document. For more on the sailing of de Grasse’s fleet, see John Laurens to GW, 24 March, and n.8 to that document.

6. See Chastellux to GW, 12 and 21 May.

7. Rochambeau later recalled: “As soon, therefore, as I had fully deciphered my dispatches, my first step was to request an interview of General Washington” (, 44; see also Rochambeau to GW, 8 and 11 May).

8. See GW to Rochambeau, 13 and 14 May, and Document III, source note; see also the entry for 13 May in , 3:363.

9. See Document I.

10. For an account of GW’s travel to Wethersfield, see , 3:367–68; see also , 1:61–62.

GW’s aide-de-camp Tench Tilghman had written Q.M. Gen. Timothy Pickering from headquarters at New Windsor on Tuesday, 15 May, about retrieving his horse, believing it “very uncertain whether he will be here in time or fit for service if he does come, as he has been almost dead with the distemper. Under these circumstances I must beg you to make another effort for me. I shall have occasion for the Horse on Friday Morning” (DNA: RG 93, manuscript file no. 26001).

11. “The Expences of a Journey to Weathersfield for the purpose of an Interview with the French Genl & Adml” amounted to $8,376½. GW also expended £35.18 in specie during this trip (Revolutionary War Expense Account, 1775–1783, DLC:GW, ser. 5). An itemization of amounts spent at different places and for various purposes can be found under May 1781 in Revolutionary War Receipt Book, 25 Feb. 1781–June 1783, DLC:GW, ser. 5.

12. The Connecticut Courant and Weekly Intelligencer (Hartford), 29 May 1781.

13. For more on the house and GW’s stay, see , 268–76; see also GW to Joseph Webb, 17 June, and Webb to GW, 30 June.

14. , 3:368.

15. , 531. The church’s large choir evidently impressed GW. See A. C. Adams, Historic Sketch of the First Church of Christ in Wethersfield … (Hartford, 1877), 16–18.

16. See Chastellux to GW, 21 May, and n.2 to that document; see also , 104.

17. The Connecticut Courant and Weekly Intelligencer (Hartford), 29 May 1781.

18. See , 531; see also , 1:346.

19. See Barras to GW, 17 May, and GW to Barras, 23 May; see also Rochambeau to GW, 8 May, and n.1 to that document.

20. See Document III.

22. For the enemy troops detached from New York and sent to the Chesapeake Bay region, see William Heath to GW, 1 May, n.1.

23. , 3:369–70; see also Document III.

24. See Document II.

25. , 51. Rochambeau later expanded: “General Washington, during this conference, had scarcely another object in view but an expedition against the island of New York, and which he persisted in considering the most capable of striking a death-blow to British domination in America. He was aware of the enemy’s forces having been thinned at this place by the detachments which had been drafted from its garrison, and sent to the south, and thought, on the assurance of several pilots, that our ships might easily pass the bar of the harbour without being lightened. He considered an expedition against Lord Cornwallis, in Chesapeak Bay, as quite a secondary object, to which there was no necessity of diverting our attention until we were quite certain of our inability to accomplish the former. After some slight discussion, it was settled, however, that as soon as the recruits, with the small convoy of the Sagittaire, should join, the French corps should proceed to unite itself to the American army opposite the island of New York, to which the combined army should then approach as near as possible, and there wait until we should hear from M. de Grasse, to whom a frigate was to be immediately dispatched” (, 45–46). For the arrival of the 50-gun Sagittaire with a convoy, see Barras to GW, 9 June, and n.5 to that document.

For detailed narratives on the conference at Wethersfield, see , 5:285–90; , 132–40; and , 111–20.

26. , 3:370–71.

27. See Document IV.

29. See GW to John Sullivan, 29 May, as well as to John Parke Custis and to Lafayette, both 31 May. Rochambeau later wrote: “[GW’s] letters were intercepted; it is believed, and all the papers repeated the report, that he spoke in those letters of the projected attack on the New York islands, with a view only to mislead the enemy’s general, and that, consequently, he was very glad that the letters had falled into the hands of the latter. There is no need of such fictions to convey the glory of this great man to posterity. His wish was really then to attack New York; and we should have carried the plan into execution if the enemy had continued to draft troops from its garrison, and if the French navy could have been brought to our assistance” (, 46). For GW’s frustration over the British interception of his letters, see GW to Lafayette, 4 June, n.1; see also GW to Samuel Huntington, 6 June, and Sullivan to GW, 11 June.

30. , 5:135–36. Clinton later wrote that “some letters from General Washington and several principal officers belonging to the French armament at Rhode Island, that were found in one of their mails just fallen into our hands, gave me to understand that the enemy had in a grand conference come to a resolution of attacking New York with all the force they could collect.

“I was well aware that for such an object as the siege of New York Mr. Washington would find no difficulty in assembling what number of troops he pleased. The Continentals immediately under himself at this period amounted to about 6000, the French troops at Rhode Island having been lately recruited to about 6000 more; and these, with the Jersey, Connecticut, and Massachusetts levies, might form an army of 20,000 men. My own force in the New York district was certainly very inadequate to this, not exceeding 9,997 fit for duty, besides about 1500 militia belonging to that city, unarmed. I had, however, such confidence in the zeal and discipline of the troops I commanded that I should have been in no pain for the issue of such an attempt as long as our fleet remained superior to that of the enemy, and preserved the communication open between me and the Chesapeake, as its cooperation would most probably effectually disconcert the enemy’s operations either against

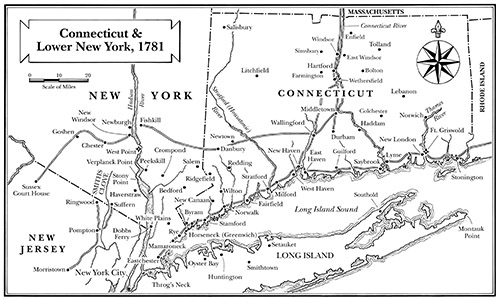

Map 4. GW and Rochambeau met on 21–22 May at Wethersfield, Conn., just south of Hartford, to plan the 1781 campaign. (Illustrated by Rick Britton. Copyright Rick Britton 2022)

me or Lord Cornwallis, whose situation I was much more apprehensive for than my own. …

“The letters we had so fortunately intercepted being written immediately after the conference held at Wethersfield between Generals Washington and Rochambeau on the operations of the approaching campaign, they had brought everything into one distinct point of view, and thereby clearly developed to us the enemy’s distressed situation and prospects. It was consequently easy to discover from them that, our operations in the Chesapeake … having greatly alarmed Mr. Washington, his chief wish had been to induce the French army and navy to join him with their whole force in an attempt against our posts there. But the consideration of their naval inferiority, the large body of troops at present collected in that quarter, and the approaching inaptitude of the time of year for military movements to the south of the Delaware were judged sufficient reasons for deferring that undertaking until a more convenient season” (, 304–5).

31. , 20:154–57, quote on 155.

32. , 2:546–47. For another British reaction to the intercepted letters, see James Robertson to Jeffrey Amherst, 12 June, in , 202–6.

33. , 104; see also , 80.

34. Rochambeau’s letters to La Luzerne are in DLC: Rochambeau Papers, vol. 9.

35. Henry Clinton to George Germain, 9–12 June, in , 20:154–57, quote on 155. For later deciphering of the conference proposals, see Document III, source note.

36. DLC: Rochambeau Papers, vol. 9.

37. DLC: Rochambeau Papers, vol. 9. For the council of war held on 31 May that determined to keep Barras’s squadron at Newport, see Barras to GW, and Rochambeau to GW, both 31 May. Since Rochambeau’s letter to Ségur on 29 May announced the council’s decision, his letter may have been backdated or completed on 31 May.

38. DLC: Rochambeau Papers, vol. 9.

39. See General Orders, 30 June; see also GW to Benjamin Lincoln, 1 July, and the source note to that document.

40. See GW and Rochambeau to de Grasse, 17 Aug. 1781, DLC:GW; see also the entry for 14 Aug. in , 3:409–10.

![University of Virginia Press [link will open in a new window] University of Virginia Press](/lib/media/rotunda-white-on-blue.png)