Alexander Hamilton to John Jay, 6 May 1794

From Alexander Hamilton

Philadelphia May 6. 1794

My Dear Sir

I send you herewith sundry papers and documents, in which you will find material information with regard to the which contain information that may be of use ^not useless^ to you in the course of ^regard to^ your mission.1

Our conversations have anticipated so much that I could say little here which would not be repetitive. I will nevertheless add a few observations

*[illegible] ^[in margin] *I had wished to have found liesure to say many things to you but my occupations permit me to offer only a few loose observations.^

We are both impressed equally strongly with the vast ^great^ importance of [a gen.?] ^a^ right adjustment of all matters of past controversy and future good understanding with G. Britain. Yet important as this object is, it will be better to do nothing— than to do any thing which will not stand the test of the severest scrutiny, and especially which may be construed into the relinquishment of a substantial right or interest.

The question ^object^ of indemnification for the injuries depredations committed on our Trade in consequence of the instructions of the 6th of November is very near the hearts & feelings of the people of this Country. The proceeding was an atrocious ^one^. It would not answer in this particular to set [damages?] with the mere appeara make any arrangement on the mere appearance of Indeminification— [illegible] If nothing substantial can be agreed upon, it will be better merely to ^best to content yourself with^ endeavouring to dispose the British Cabinet of their own accord, to go as far as they think fit leaving the UStates at full liberty to act afterwards as they think ^[illegible]^ ^deem^ proper. I am however ^still^ of opinion that [bona fi] substantial indemnification on the principles of the [last?] instruction of January 8 may in the last resort be admissible.2

What I have said goes upon the Idea of the affair of indemnification standing alone. If you can effect solid arrangements with regard to the points unexecuted of the Treaty of peace, the question of indeminification may be managed with less rigor… and may be still more laxly disposed of ^treated dealt with—^ if a truly beneficial treaty of Commerce (embracing privileges in the West India Islands) can be established— It will be worth the while of the Government of this Country, in such case, to satisfy, itself & its own citizens, who have suffered.3

The principle of GBritain is that a neutral nation ought not to be permitted to carry on in time ^of War^ a commerce with a belligerent Nation at war which it could not carry on ^with that Nation^ in time of peace— It is not without importance in this question4— that the peace ^permanent^ system of France allowed access to her Islands to our vessels ^access to her Islands^ with a variety of our principal staples & allowed us to take from thence some of their products— & that by frequent colonial regulations this privilege extended to almost all other articles.5

The great political & commercial considerations which ought to influence ^the p the conduct of^ G.B. ^in^ her conduct towards this country are familiar to you. They are strengthened by the ^last^ ^late increasing^ acquisitions in the West Indies, if these shall be ultimately confirmed, which certainly creates seem to create an absolute dependence on us for supply.

I see not how it can be disputed with you that this Country in a commercial sense is more important to G. Britain than any other— The articles she takes from ^us^ are certainly precious to her, paculiarly important ^perhaps essential^ to the ordinary ordinary subsistence of her Islands— not import unimportant to her own subsistence occasionally, always very important to her manufactures, and of real consequence to her revenue.6 As a Consumer the paper A will shew that we stand unrivalled. We now consume at least a ^of her exports from a milion to milion & a half^ Sterling more than any in value than any other ^foreign^ country & while the consumption of other countries from obvious causes is likely to be stationary that of this country is increasing and for a long, long, series of years, will increase rapidly. This Our manufactures are no doubt progressive. But our population and means progress so much faster, that our call for ^need of^ ^demand for manufactured^ supply far outgoes the the progress of our internal faculty to manufacture. Nor can this cease to be the case for any calculable period of time.

How unwise then in G Britain to suffer such a state of things to remain exposed to the hazard of constant interruption & derangement by not settl fixing on the basis of a good Treaty the principles on which it should continue?

Among the considerations which ought to lead her to a Treaty is the obtaining a renunciation of all pretension of right to sequester or confiscate debts by way of reprisal7 &c. though I have no doubt this is the modern law of Nations. Yet the point in her of right cannot be considered so clearly absolutely settled as not to make it interesting to fix it by Treaty.

There is ^a^ fact, which has escaped observation in this country and which as there has existed much too much disposition to [reduce?][illegible]

^convulse^ our Trade into disorder. I have not thought it prudent to bring into view) which it is interesting you should be apprised of— An Act of Parliament 27 George 3d Chapter 27 allows foreign European Vessels single decked & not exceeding seventy Tons burthen to carry to certain Ports in the British West Indies particular articles therein enumerated and also to take from thence certain articles.8

This consequently puts an end to the question of precedent, which is so strongly objected to ^urged against^ a departure from The British Navigation Act in our favour; since it gives the precedent of such a departure in favour of others and to our exclusion, a circumstance worthy of particular notice. The relative situ Our relative Situation gives us a stronger plea, for an exception in our favour, than any other Nation can urge.*

^[in margin] *In Paper B the idea of a Treaty of commerce on the footing of the status quo for a small amount of ye short period (say five years) is brought into view. I should understand this as admissible only in the [event of a] satisfactory arrangement with regard to the points unexecuted of the Treaty of Peace.^

The Navigation of the Mississippi is to us an object of immense consequence. Besides other considerations connected with it, if the Government of the UStates can procure & secure ^the enjoyment of^ it to our Western Country, it will be an infinitely strong link of Union between that Country & the Atlantic States— As its preservation will depend on the naval resources of the Atlantic States the Western Country cannot but feel that this essential interest depends on its remaining firmly united with them.

If any thing could be done with G Britain to increase our chances of for the speedy enjoyment of this right it would be in my judgment a very valuable ingredient in any arrangement you could make. Nor is Great Britain without a great interest in the Question, if the arrangement shall give to her a participation in that Navigation & a Treaty of Commerce shall admit her advantagously into this vast ^large^ field of commercial adventure.9

May not an article be formed that

May it not be possible to obtain a Guarantee of our right in this particular from G Britain on the condition of mutual enjoyment of a trade on the same terms ^as to^ [illegible] our Atlantic Ports?10

This is a delicate subject not well matured on my part but which may be ^not un^ worthy of your consideration. ^in my mind*.^ ^[in margin] *It is the more delicate as there is at the moment a negotiation pending with Spain,11 in a position I believe not altogether unpromising, and ill use might be made

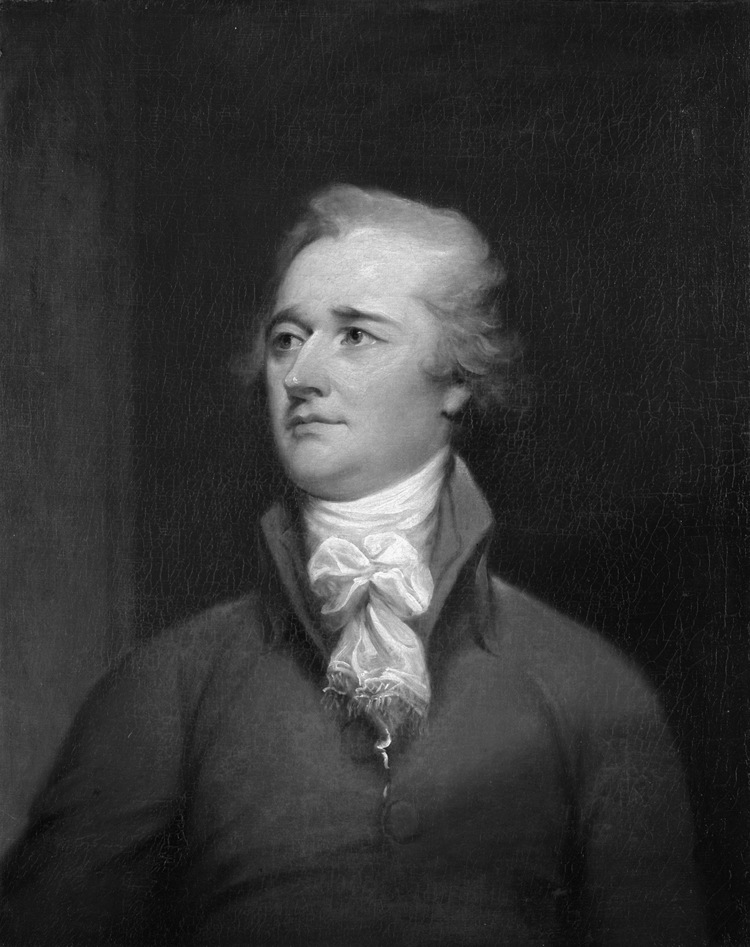

Alexander Hamilton, by John Trumbull, 1832. (Yale University Art Gallery, Trumbull Collection, 1832.11)

With the most cordial of fervent wishes for your health, comfort & success I remain Dr Sir Your Affectionate & Obedient ser

AAA But you ^will^ discover from your instructions that the opinion which has prevailed is that such a Treaty of commerce ought not to be concluded without previous reference here for further instruction. It is desireable however of the to push the British Ministry in this respect to a result that the extent of their views may be ascertained.

John Jay Esqr

Dft, DLC: Hamilton (EJ: 10765). , 16: 381–85.

1. Enclosures not found.

2. On the Order in Council of 6 Nov. 1793, which ordered the seizure of all ships engaged in trade with the French colonies, and the Order of 8 Jan., which revoked it, see the editorial note “The Jay Treaty: Appointment and Instructions,” above.

3. Although JJ advanced the idea of concessions on the West Indies trade as compensation for Britain’s retention of the posts, there is no record of his having suggested a commercial treaty as compensation for British depredations on American trade. See JJ to ER, 13 Sept. 1794, LS, DNA: Jay Despatches, 1794–95 (EJ: 04312); C, NHi: King (EJ: 04444); LbkC, NNC: JJ Lbk. 8; , 4: 60–114.

4. For Hammond’s assertion, in the course of a conversation with AH [15–16 Apr.] that the Order in Council of 6 Nov. was not an innovation, see the editorial note “The Jay Treaty: Appointment and Instructions,” above; and , 16: 281–86.

5. France’s decree of 30 Aug. 1784, which regulated American trade with the French West Indies, expanded the number of free ports in the French West Indies from two to seven, to which only foreign vessels larger than sixty tons would be admitted. Smaller American vessels were customary in the trade. While the decree expanded the list of items that could be imported by the islands, it still prohibited foreign grain and flour, and severely limited the items that could be exported on foreign vessels, thereby making the trade unattractive. See , 8: 684–87, 697.

6. For an earlier expression of these arguments, see Gouverneur Morris to JJ, 25 Sept. 1783, , 8: 547.

7. See Art. 8 of JJ’s draft treaty of 30 Sept., D, with minor corrections and an added paragraph in JJ’s hand, UkLPR: FO: 95/512 (EJ: 05006). This “project” was enclosed in JJ’s letter to Grenville of 30 Sept., Dft, UkWC-A (EJ: 00048); C, NNC (EJ: 08499).

On sequestration of debts as a suggested reprisal for British attacks on American trade, see the editorial note “The Jay Treaty: Appointment and Instructions,” above.

8. For the text of this act, see , 16: 384. Article 12 of the Jay Treaty permitted the trade in allowed articles to American vessels of no more than 70 tons, but it was rejected by the U.S. Senate because of other trade restrictions it imposed. See , 355.

9. Article 4 of the Jay Treaty established a boundary commission that determined that the upper reaches of the Mississippi did not extend into British territory, thereby precluding British navigation of the river. For Lord Hawkesbury’s comments on the volume of trade British traders were already conducting on the Mississippi and on the importance of maintaining access to the region, see Bradford Perkins, “Lord Hawkesbury and the Jay-Grenville Negotiations,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 40, no. 2 (Sept. 1953), 294–95. Charles Jenkinson, Lord Hawkesbury (1729–1808) was the president of the Board of Trade and a member of Pitt’s cabinet.

10. See Art. 9 of JJ’s draft treaty, 30 Sept., cited in note 7, above. For his suggestion that the treaty could be used to open the Mississippi and rivers running through Florida to the United States, see JJ to ER, 10 Dec. 1794, LS, marked “Duplicate,” with the sentence on the Mississippi enciphered and decoded, DNA: Jay Despatches, 1794–95 (EJ: 04343); APS: FR, 1: 509.

11. In 1792, GW had appointed William Short and William Carmichael joint commissioners to negotiate opening the Mississippi to American navigation, a treaty of commerce, and all other outstanding difficulties between the two nations. See , 9: 384, 423–24, 10: 50–57, 132.

12. During the Nootka Sound Controversy, Grenville had suggested to Dorchester that the United States might be persuaded to ally with Britain against Spain as a means of opening the Mississippi to American trade. See GW to JJ and the Heads of Departments, 27 Aug. 1790, above. In 1794, however, because it was suspected that the border line drawn between Canada and the United States fell above the northern reaches of the river, Grenville was more concerned about insuring British access to the Mississippi than in aiding the United States to procure the right to navigate it. News that JJ had signed the treaty with Britain, however, contributed greatly to Spain’s willingness to open navigation of the Mississippi River to the United States in the Treaty of San Lorenzo, signed by Thomas Pinckney on 27 Oct. 1795.

JJ’s Draft Treaty and the final version of the treaty restated the provision of the Treaty of 1783 providing that the river would be open to both parties. Article III of the treaty further provided that “all the ports and places on its Eastern side, to whichsoever of the parties belonging, may freely be resorted to, and used by both parties, in as ample a manner as any of the Atlantic Ports or Places of the United States, or any of the Ports or Places of His Majesty in Great Britain.”

![University of Virginia Press [link will open in a new window] University of Virginia Press](/lib/media/rotunda-white-on-blue.png)