To George Washington from Major General Philemon Dickinson, 28 June 1778

From Major General Philemon Dickinson

¼ past 4, OClock A.M.

June 28th 1778 [Monmouth, N.J.]

Dr Sir

A Major who was on Duty on the Lines last Night, this moment informs me, that the Enemy are in Motion—marching off—my Picket at the Mill1 drove the Enemy of[f] last Eveng & kept the Ground. I have the honor to be Your Excellency’s Most Ob. St

Philemon Dickinson

I am moving down two or three hundred Men to amuse & detain them—& have parties out to gain Intelligence—shall take down the whole of my troops, as soon, as they can be collected—a second Express from the Mill Picket informs me, they moved as early as 4, OClock.

ALS, DLC:GW.

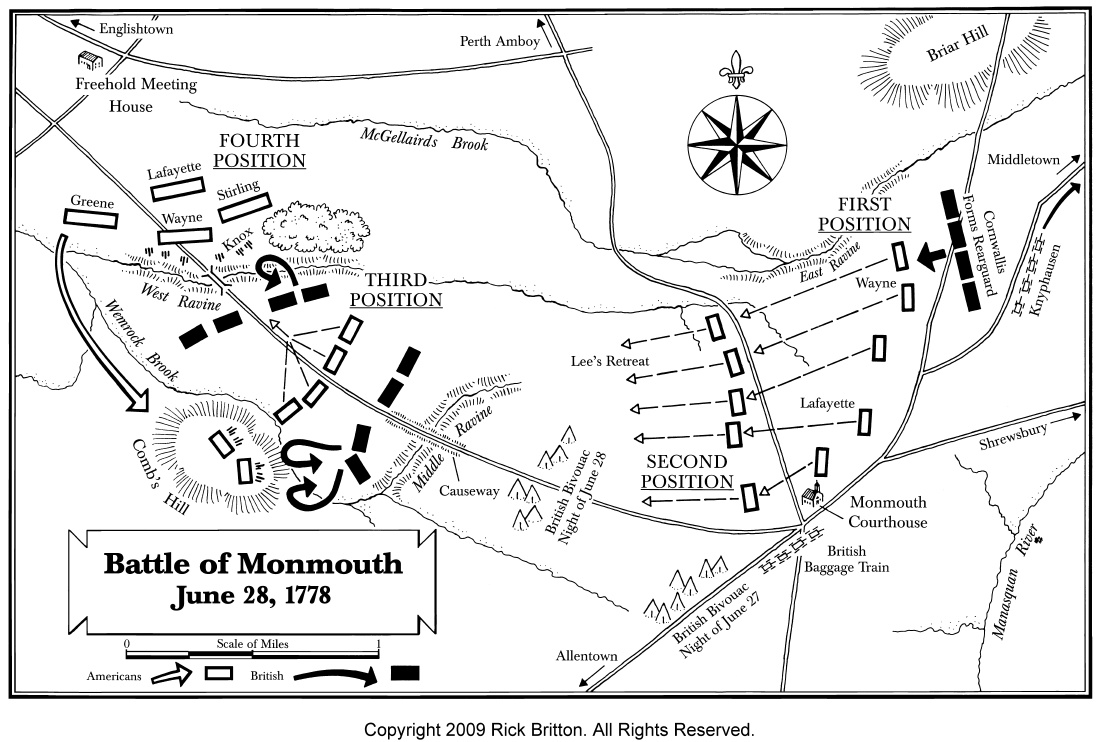

Monmouth Court House, also called Freehold, was a small village of about forty houses situated at a major crossroads (see note 1 to Col. Stephen Moylan’s first letter to GW of 27 June). The terrain that surrounded the village was easily defensible. One mile north of the courthouse, between the roads leading to Middletown and Perth Amboy, was a stretch of rough, boggy land known as the East Ravine. To the west, the road from the courthouse to Englishtown traversed two miles of woods, fields, and thick underbrush before crossing the Middle Ravine. From there the road continued west for about another mile and entered the marshy West Ravine, where it crossed Wemrock Brook over a bridge. South of the Middle and West Ravines was more rough terrain, where hills alternated with streams and bogs.

The British began leaving Monmouth in two divisions in the early morning of 28 June. The first division, composed of about four thousand troops and the baggage train under General Knyphausen, stirred between 3:00 and 4:00 a.m. and marched northeast on the road to Middletown. The second division, numbering 6,000 mostly British troops under Clinton and Cornwallis, followed at about 5:00 a.m. in the same direction. Knyphausen’s vanguard marched five miles during the next four hours, but his baggage train was still straggling all the way back to Monmouth Court House when the “two or three hundred Men” that Dickinson

Maj. Gen. Charles Lee’s detachment of 5,000 men meanwhile decamped from Englishtown at about 7:00 a.m. and marched southeast, crossing the West and Middle Ravines before leaving the road and marching east cross-country. Lee’s troops then crossed the Perth Amboy Road and continued marching east along the East Ravine, leaving Monmouth Court House to the south. As he advanced, Lee received an intelligence report from Capt. John Heard, the final words of which apparently are missing: “the Enemies frunt is three miles from the monmouth Court House on the Shrewsbury road there is two Roads one Leads to Middletown & one to Shrewsbury their was a party of horse & foot out this morning I am agoing to try if I Can Get in there frunt By the partys being out this morning I Do not think they have March three Miles from the” (DLC:GW).

By midmorning Lee’s troops, who had struggled through the countryside in temperatures approaching 100 degrees, were arrayed in a haphazard line facing the Briar Hill Road, with the East Ravine to their left rear and Monmouth Court House to their right rear. Here they joined elements of Dickinson’s militia and probed the British covering force, which by this time consisted of three infantry brigades. Lee toyed with a number of methods of dislodging the enemy and sparred with them ineffectually for about two hours before attempting a complicated pincer movement that would, he hoped, cut off the entire British rear guard. But it was not to be. His units became hopelessly entangled as they advanced and eventually had to break off the attack. By then Knyphausen’s division and the baggage train had scurried out of range down the Middletown Road, and Clinton had assembled Cornwallis’s entire division of 6,000 men to face Lee. As the British advanced at about 1:00 p.m., some American units tried to reposition themselves, but their movements were mistaken for withdrawals by other units, which responded by retreating in earnest. Soon the entire force was in flight, with Lee unable to control it.

Lee’s force retreated southwest through Monmouth Court House and then west along the Englishtown Road. The American force became further dispersed in the process, and by the time it reached the Middle Ravine, Major General Lafayette and brigadier generals Charles Scott and Anthony Wayne led their commands more or less independently, without paying much regard to Lee. Indeed, Scott and Wayne were so angry with Lee that they avoided speaking to him. Cornwallis’s troops pursued, but the midafternoon heat enervated them so badly that it was all they could do to keep up.

GW spent the morning marching from Penelopen toward Monmouth Court House with his own force of 6,000 troops, arranged in two divisions under major generals Stirling and Nathanael Greene. Just before he reached the West Ravine, GW received inaccurate intelligence of a possible flanking movement to his right, and to meet it he ordered Greene to file off in that direction before continuing east. As GW resumed the advance, he encountered the first signs of Lee’s retreat in the form of some panic-stricken stragglers fleeing toward Englishtown. Soon he met Lee himself and demanded the meaning of the retreat. Lee hesitated and then replied “that from a variety of contradictory intelligence, and that from his orders not being obeyed, matters were thrown into confusion, and that he did not chuse to beard the British army with troops in such a situation. He said besides, the thing [the attack on Clinton, which Lee had never endorsed] was against his own opinion. General Washington answered, whatever his opinion might have been, he expected his orders would have been obeyed, and then rode on towards the rear of the retreating troops” (, 3:81). Stories that GW cursed Lee probably are untrue.

GW crossed the West Ravine, ordered Wayne to deploy the 3d Maryland and 3d Pennsylvania Regiments as a rear guard in a nearby copse, and then returned and told Lee to join Wayne with whatever troops he could muster. Stirling’s division and Brig. Gen. Henry Knox’s artillery meanwhile took up positions on the western slopes of the ravine while Greene’s division occupied Comb’s Hill, about seven hundred yards to the south. It took an hour of heavy fighting for Clinton to drive Lee and Wayne from their positions, and by midafternoon the remainder of Lee’s detachment had retreated across the bridge that spanned the West Ravine. GW ordered Lee to take his battered force back to Englishtown.

After an artillery duel that lasted about two hours, Clinton launched an attack across the West Ravine in the late afternoon. But the Americans were well entrenched, and after a fight that seesawed back and forth across the ravine for an hour or so, the troops were back in their original positions. An attempt by Cornwallis to dislodge Greene from Comb’s Hill likewise ended in an impasse. By 6:00 p.m. both sides were exhausted, and Clinton withdrew his troops half a mile in order to stay out of range of the American artillery. GW spent the night under a cloak next to Lafayette, with whom he discussed plans to attack in the morning. But at midnight Clinton’s troops left their campfires burning and withdrew toward Middletown. By sunrise on 29 June the British were well on the road to Middletown and Sandy Hook, N.J., where they began embarking for New York City on 1 July.

Both sides claimed victory in the encounter (see General Orders, 29 June, and Hastings, Clinton Papers, 97), but although British casualties were slightly higher, the Battle of Monmouth is probably best described as a draw. A modern estimate based on contemporary sources puts American casualties at 69 killed, 161 wounded, and 95 missing, along with 37 dead of heatstroke, against Clinton’s official report of 147 killed, 170 wounded, and 64 missing, figures that apparently did not include Germans (Peckham, Toll of Independence, 52). For American accounts of the battle, see especially , 3:1–208 (containing testimony taken during Lee’s subsequent court-martial); , 126–29; McHenry, Journal, 5–8; 83; , 9; and 110; for British accounts, see , 177; , 78–81; , 135–36; , 186–87; , 193–95; and , 67–68.

1. Craig’s Mills were located a few miles southwest of Monmouth Court House at what is now Millhurst in Manalapan Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey. An inhabitant of Freehold who apparently served in the New Jersey militia was stationed at the mill picket on the morning of 28 June and recalled in a letter that the British “surprised our picket at Craig’s mill, and put them to flight; and, I believe, one half hour would have destroyed us in this settlement, root and branch, had not General Dickinson come directly into it at the very time; and by that means saved us” (Pennsylvania Gazette [Philadelphia], 14 July 1778).

![University of Virginia Press [link will open in a new window] University of Virginia Press](/lib/media/rotunda-white-on-blue.png)