From George Washington to Colonel Arendt, 23 September 1777

To Colonel Arendt

Camp [near Pottsgrove, Pa.] Septr 23d 1777

Sir

It is of the utmost importance to prevent the Enemy’s Land Forces and Fleet from forming a junction, which it is almost morally certain they will attempt by seizing on Fort Island below Philadelphia, if it is possible, and thereby gain the Navigation of the Delaware by weighing and removing the Chivaux Defrize, which have been sunk for that purpose. This Post—(Fort Island) if maintained will be of the last consequence, and will effectually hinder them from Union. I therefore appoint you to the command of It, and desire that you will repair thither immediately. The defence is extremely interesting to the United States, and I am hopefull will be attended with much honor to yourself and advantages to them. There are Troops there now, and a Detachment to reinforce them will imediately march from this Army. I have nothing further to add than my wishes for your success and to assure you, that I am with esteem Sir Yr Most Obedt Servant

G.W.

Df, in Robert Hanson Harrison’s writing, DLC:GW; Varick transcript, DLC:GW.

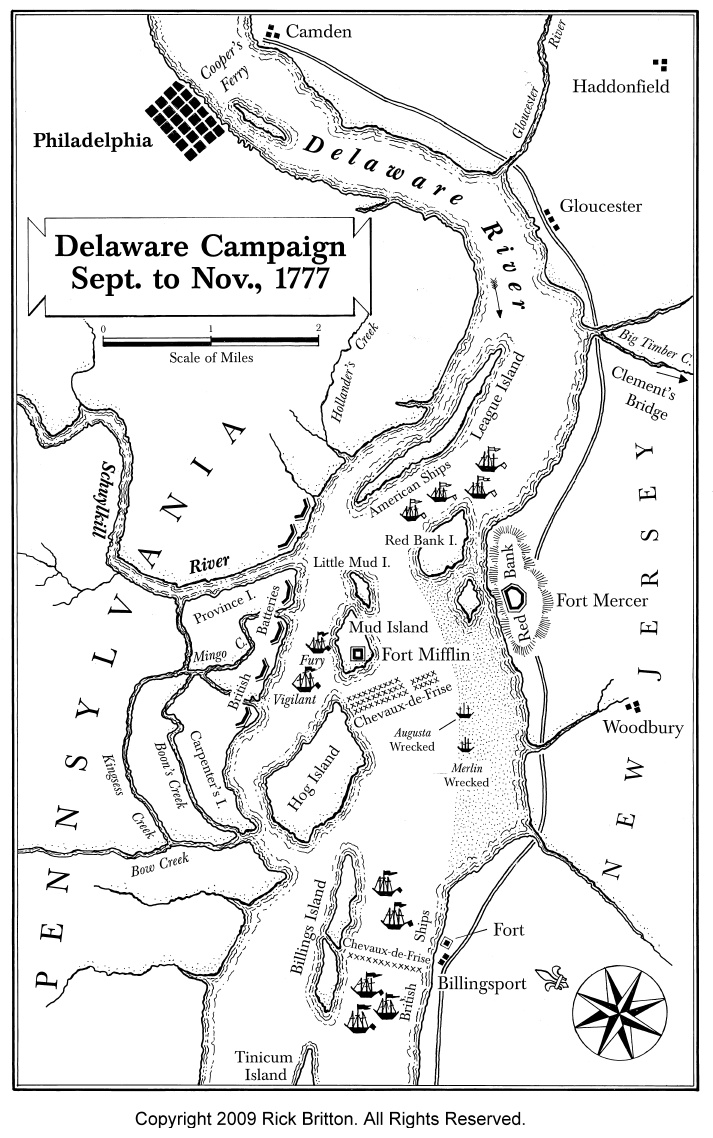

Although by this date GW accepted the inevitability of the British occupation of Philadelphia that occurred three days later, he thought that Howe’s army might yet be defeated if he could prevent it from being supplied at Philadelphia by land or water. A strategically important portion of the city’s most vital supply route, the Delaware River, remained in American hands, and GW took steps to try to keep a stranglehold on it by garrisoning Fort Mifflin, a low-lying defensive work that stood on Mud or Fort Island in the Delaware near the mouth of the Schuylkill River about seven miles below Philadelphia (map 3).

Fort Mifflin’s guns covered several lines of chevaux-de-frise, iron-tipped underwater obstructions that the Americans had sunk in the Delaware’s main channel near Mud and Hog islands to impede the passage of British warships and transports up the river. Fort Mercer at Red Bank, N.J., located about a mile southeast of

After inspecting the Delaware forts and obstructions in early August, GW had recommended to Congress that the effort to defend the river should be concentrated at Fort Mifflin because British warships would find it much more difficult to break through the upper obstructions than the lower ones and because in the event of an attack Fort Mifflin would not be as exposed to enemy artillery fire from the surrounding terrain as the fort at Billingsport would be (see GW to Hancock, 10 Aug. 1777). During the intervening weeks, however, little had been done toward completing the works at either fort, and both of them remained thinly manned. The garrison at Fort Mifflin consisted of about sixty invalids and sixty untrained militia artillerymen, all under the command of Col. Lewis Nicola, and at the Billingsport fort Col. William Bradford commanded slightly more than one hundred Pennsylvania militiamen.

To remedy the situation at Fort Mifflin, GW on this date appointed Colonel Arendt as commanding officer in place of Nicola, and he ordered Lt. Col. Samuel Smith to form a new and stronger garrison with his detachment of about two hundred Continentals (see GW to Smith, this date). GW also directed Commo. John Hazelwood to reinforce the fort with two to three hundred sailors from his fleet until the Continentals arrived and to assist in its defense by stationing armed row galleys in the surrounding waters (see Instructions to Hazelwood, this date).

Lieutenant Colonel Smith arrived at Fort Mifflin with his men on the night of 26 Sept. (see Smith to GW, 27 Sept.). Because Colonel Arendt was chronically ill during the next several weeks, Smith commanded the fort for most of the time that it was under attack by the British. Arendt was able to be present at and command Fort Mifflin for only a few days in late October, and then illness forced him to withdraw, leaving it again under Smith’s command until Smith was wounded on 11 Nov., four days before the fort was abandoned (see GW to Arendt and to Smith, 18 Oct., Arendt to GW, 20 Oct., GW to Smith, 28 Oct., and Smith to GW, 26, 30 Oct., 12, 15 Nov.).

The Billingsport fort fell to the British on 2 Oct., and by 14 Oct. the lower obstructions had been cleared effectively enough to permit British ships to pass through them with regularity. Fort Mifflin held out until the night of 15–16 Nov., when it was evacuated and left to be occupied by the British the following day. Fort Mercer, which depended on Fort Mifflin for support, had to be abandoned on the night of 20–21 Nov., giving the British complete control of the lower Delaware at last. In a diary entry for 21 Nov., General Howe’s aide-de-camp Captain Muenchhausen wrote that “a narrow passage through the [upper] cheveaux de frise, which was unknown to us, but was closed up with a very strong chain, was opened by our ships today, so that they can come up [to Philadelphia] now” (, 44). That event, which guaranteed the British an essentially inviolable supply route to the city, put an end to GW’s hopes for isolating Howe’s army and starving it into submission.

While acknowledging the bravery of the troops who had withstood the British attacks for so long, GW believed that the British victory on the Delaware was at least in part attributable to Gen. Horatio Gates’s delay in sending reinforcements south after his victory at Saratoga, N.Y. (see GW to John Augustine Washington, 26 Nov. 1777). Some contemporaries and historians have argued that the Pennsylvania government and GW himself shared some of the blame for not improving and reinforcing the Delaware defenses before September 1777. The failure of the New Jersey and Pennsylvania militias to come out in sufficient numbers and the lack of interservice cooperation between the Fort Mifflin garrison and Commodore Hazelwood’s fleet also undoubtedly contributed to the American loss of the battle for the lower Delaware and the subsequent British ability to consolidate their seemingly permanent hold on Philadelphia.

![University of Virginia Press [link will open in a new window] University of Virginia Press](/lib/media/rotunda-white-on-blue.png)