To Benjamin Franklin from William Henly, 28 November 1772

From [William Henly]

AD and draft: American Philosophical Society; printed in the Royal Society, Philosophical Transactions …, LXIV (1774), 403–6.7

Novr. 28. 1772.

The Description and use, of a new Conductor for Experiments in Electricity,8 contrived by Mr. H——and executed by Mr. Edward Nairne.

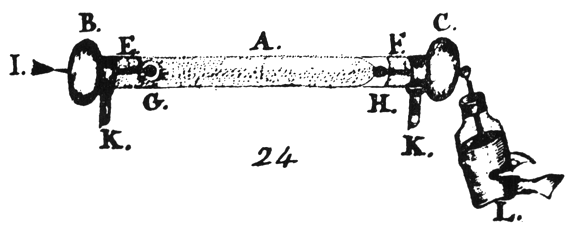

| A. | A Tube of Glass 2 feet in length, 2 Inches diameter. |

| B. C. | Balls with a ferril of Brass (2 Inches long, to each) which are to be cemented to the ends of the tube, and made Air tight. One of the plates which are solder’d to the ferrils, hath a small hole dril’d through it, by which the Air is to be exhausted; it is cover’d by a strong valve well secured, and conceal’d by the brass ball. |

| [E.] F. | A Coating of Cement from the Brass caps, 3 Inches upon the glass at each end, to prevent the moisture from adhering to the tube, and conducting the Electricity over its outer surface.9 |

| G. H. | Balls of Brass ½ Inch diameter fixed upon wires which project into the tube 5/2 Inches from the plate at the end of it.1 |

| I. | A fine point to collect the Electricity from the globe [in the margin:] or to disperse it in the Air as in the above experiment.2 |

| K. K. | Supporters of sealing wax, upon which the Glass Conductor is to be mounted for experiments. |

| L. | A Bottle properly prepared for electrical experiments and charged positively. |

| N.B. The dots in the tube are intended to represent the appearance of the Electricity in it. |

The use of the Glass Conductor

The Glass tube thus furnished and mounted, being properly exhausted, and perfectly dry, will Act in all respects like one of Metal: and the Electrometer being placed upon the Brass ball C. will answer to the charge of a Jar or Battery exactly. But the principal use of this Instrument is to ascertain the direction of the Electric matter, as it passes through it; which end it compleatly answers in the manner following. Place the collecting point before the Globe, and sit a bottle with its Knob in contact with the Ball C. of the Conductor, or hang a chain &c. from thence to the table, and the Ball H. in the Tube (on working the Machine,) becomes entirly enveloped in a dense white Atmosphere of Electricity. If the point I. of the Conductor be brought nearly into contact with an insulated Rubber, and a communication be made from the opposite end to the Earth; the ball G. in the tube, will be surrounded with the Atmosphere. If the bottle L. be charged positively and its Knob be applied as in the figure the Atmosphere will be upon G. But charge the Bottle negatively and apply it as before, and the Atmosphere will then appear upon H.

Conjectures on these phenomena.

It is supposed that the impelling power of the Globe, or the Knob of a positively charged bottle, drives the particles of the Electricity through the substance of the Ball, wire &c. (with which they are in contact,) with great velocity, and [moving?] in a straight Line; But the Electricity having enter’d the vacuum, the repulsion of its particles immediately takes place, and the tube is instantly fill’d with Light.3 The dense white Atmosphere upon the opposite Ball is imagin’d to proceed from this cause, for as every particle is supposed to be in a state of repellency with respect to its next neighbour, and as the Vacuum gives them a free liberty of expanding themselves, or standing at their greatest distance from each other: they will not enter the opposite ball in the tube in a point or small space as they do in the open Air, but (as before observed,) having free liberty to expand themselves, their natural property of repelling each other, causes them actually to do so, and thus the Wire and ball, becomes illumin’d with a very dense Atmosphere of the particles of Electricity, which they enter in all parts, at the same time, in order to their conveyance into those bodies, placed to receive them at the end of the Brass work.

By this simple and easy process, may an ocular demonstration be at all times given, of the truth and propriety of Dr. Franklins hypothesis of the Leiden Bottle &c.4 And if his Doctrines are but embraced, till his Opponents bring as good proofs of their being erroneous; I flatter myself that Learned, Candid and Ingenious Gentleman, will scarcely wish them to be retained longer.

Mr. Henly sends his most grateful acknowledgments of Dr. Franklins favour of this day, and assures him the injunctions in his Card shall be stric[tly complied?] with. Mr. H. earnestly hopes to hear o[f the health?] of his worthy Friend and the whole family.

7. The three versions were written in the order in which we list them, and differ with each other in some details. Henly altered the design of his conductor as he worked with it, and a plate in the Phil. Trans. shows the fully developed instrument. We publish the AD with its illustration, and silently supply from the printed text, where possible, words that are missing in the original. It and the later draft, both in Henly’s hand, are badly damaged.

8. The novelty of the conductor was that it was transparent, so that the apparent direction of flow of the electrical fluid could be observed. Henly’s brain child may well have been descended from the apparatus devised by Canton and others, for which see above, XVI, 112 n, and Priestley, History, I, 349–54. BF had discussed with his friend the plans for the instrument; see Henly’s letter above, under Oct. 28.

9. In the Phil. Trans. version the cement, and therefore this sentence, are omitted.

1. In the Phil. Trans. version the diameter of the balls is increased to ⅝” and 5/2 (or 5½; the numerals are obscure) becomes 2½.

2. This experiment is probably the “beautiful analysis of the Leyden phial” that Henly described in his published paper (pp. 400–1); in that case the AD must originally have been part of a longer document.

3. From this point to the end of the paragraph the Phil. Trans. version is markedly different; the principal change in substance is that the light is attributed to the small portion of air remaining in the tube.

4. The Phil. Trans. text ends here, presumably because the following sentence, which was included in Henly’s later draft as well, was considered too provocative.

![University of Virginia Press [link will open in a new window] University of Virginia Press](/lib/media/rotunda-white-on-blue.png)